Cardiff scientists look to discover how the deadliest common cancer develops in its early stages

Researchers at Cardiff University have been awarded almost £100,000 by Pancreatic Cancer UK to study how changes in a gene called ‘KRAS’ helps the deadliest common cancer develop.

We have awarded almost £100,000 to researchers at Cardiff University to study how changes in a gene called ‘KRAS’ helps the deadliest common cancer develop. Around 90% of all cases of pancreatic cancer start with changes to the KRAS gene. By studying the earliest stages of the disease, researchers hope to find a way to identify it before a tumour forms, ultimately improving early detection and survival rates.

Pancreatic cancer is the deadliest common cancer; more than half of those diagnosed die within three months of diagnosis. Its vague symptoms like stomach and back pain, unexplained weight-loss and indigestion, are common to other less serious conditions and currently there is no diagnostic tool to help healthcare professionals detect the disease. Tragically as a result, 80% of people not diagnosed until after the disease has spread and lifesaving treatment is no longer possible.

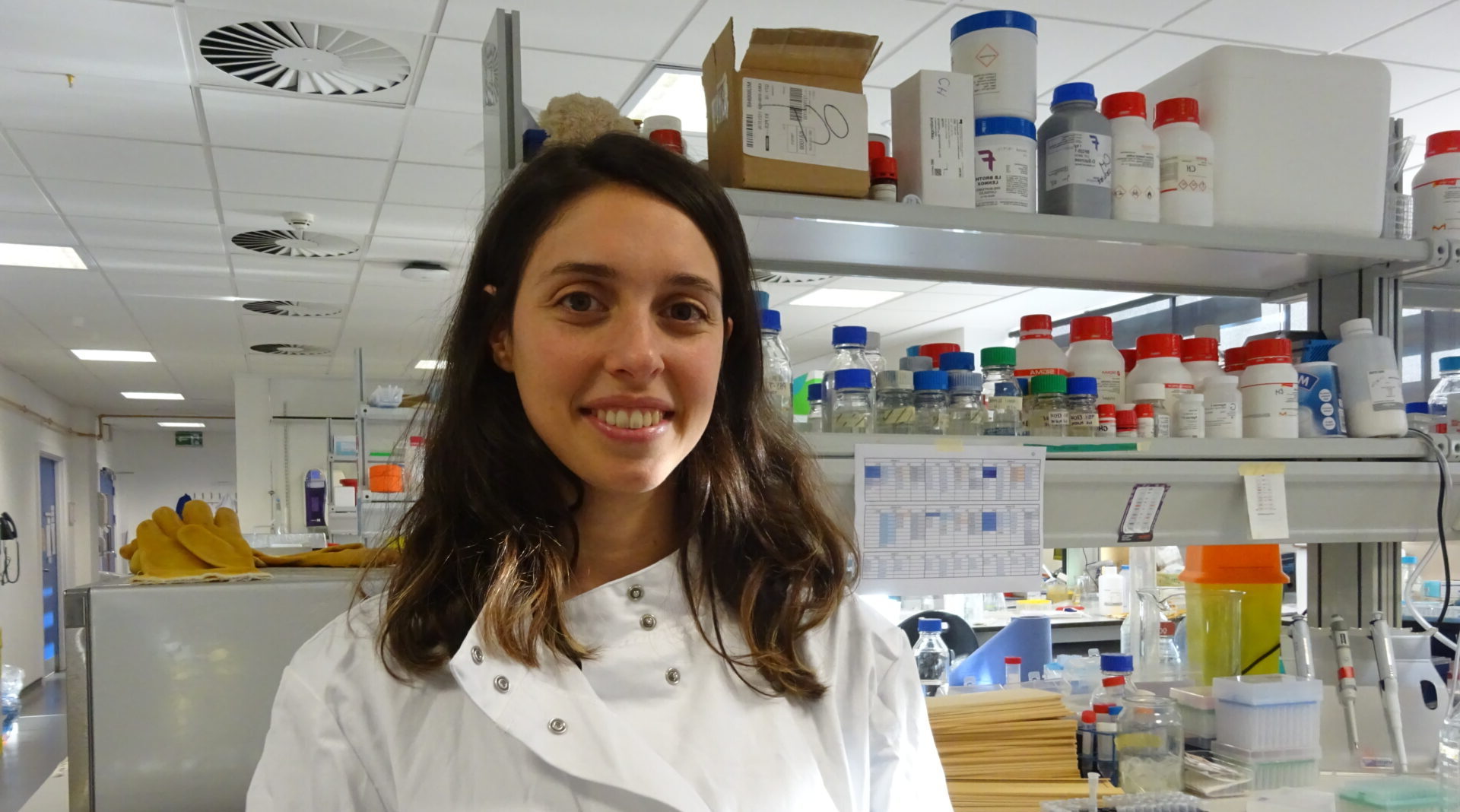

We have awarded £99,396 to the project, headed by Dr Beatriz Salvador with the aim to understand how pancreatic cancer develops in its infancy. The team will study how cells with KRAS changes interact with other cells and cause them to form pre-cancerous growths.

"If we can find the cancer before it starts, we might be able to prevent it.”

Previous research has only ever been carried out on models where KRAS changes were evident in every cell. However, recent experiments from Dr Salvador’s lab suggest that pre-cancerous growths also contain cells without KRAS mutations. Using these findings, the Cardiff team have developed a new more accurate model which they will use, along with human tissue samples, to uncover how cells interact with each other as pancreatic cancer progresses. Researchers hope the findings will shed light on how the deadliest common cancer develops in its earliest stages, before a tumour is formed, opening the door to effective ways to detect the disease.

Cardiff resident and NHS worker, Elissa Lewis knows how important early detection of pancreatic cancer is to survival after losing both her mum and brother to the disease. Around 1999, her mum, Mavis began to lose weight, struggle with acid reflux and experience abdominal pain. Her doctor initially thought it was irritable bowel syndrome, and she was given medication, but nothing improved. After going back-and-forth to her GP for at least a year, she decided to see a private consultant. They ordered a scan and biopsy, which confirmed she had pancreatic cancer.

Elissa, 60 said: “By the time she got her diagnosis, it was stage four, terminal. Nothing could be done. It was such a massive blow to our family. We knew pancreatic cancer was a bad one to get – hard to detect and often untreatable due to this.”

Mavis had chemotherapy to extend the time she had left with her family and young grandchildren. She died aged 59, just 11 months after diagnosis. Her experience would be echoed 15 years later, in 2016, when Elissa’s brother, Mark began to experience similar symptoms. He saw his GP several times and then Mark insisted they do a scan which revealed he also had stage four pancreatic cancer.

Elissa said: “I can’t even begin to describe the devastation that this news brought to our family. I remember Mark telling me, my sisters and his wife; we all just held each other and cried. It was a terrible day.”

Like Mavis, Mark had palliative chemotherapy to give him more time with his family, including his young children. He died, 11 months after diagnosis, aged 52.

“Both my mum and my brother desperately wanted to live. They were full of life. They wanted to hold onto any time left with us that they could. Hopefully research like this will mean other families get more time in the future.”

Dr Salvador and the team will use microscopy techniques to view the collected tissue samples in 3D, helping them to determine which cells have KRAS mutations at different times during cancer development. They will also use a cutting-edge technique to examine which molecules are being made by each cell, and where this is happening, providing a more accurate depiction of what is taking place inside the cells as the disease develops.

Dr Beatriz Salvador, based at the European Cancer Stem Cell Research Institute at Cardiff University, said:

“To create better ways to find pancreatic cancer early, we need to learn more about how it starts. We are studying what makes the disease begin, and this knowledge will help us develop tests that can spot people who are at high risk of developing cancer. If we can find the cancer before it starts, we might be able to prevent it.”

Dr Chris Macdonald, Head of Research at Pancreatic Cancer UK, said:

“Pancreatic cancer is tough to diagnose and treat. In most cases, the disease isn’t found until after it has spread, at which stage there are no effective treatments. Currently, surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for the disease, yet just 10% are eligible for it.

“The findings from this research could transform the future for people with pancreatic cancer. Studying early changes that take place years before a tumour even has a chance to develop could give us an exciting window of opportunity to one day stop the disease in its tracks, at the very earliest stages. Not only could this help detect the deadliest common cancer, but it could also open the door for more effective, targeted treatments.”