Vérène’s story focuses on cachexia. This is extreme weight loss that may affect people with advanced cancer. People lose both fat and muscle. We have information about weight loss in the last few months and weeks of life. We also have more general information about weight loss and pancreatic cancer.

Vérène & her husband

Vérène’s husband sadly passed away from pancreatic cancer in February 2021. They both loved good food, but towards the end of his life he struggled to eat due to digestive symptoms caused by the cancer. Vérène talks about the emotional impact of the worry surrounding his loss of appetite, his extreme weight loss at the end of life, and how they coped by finding acceptance.

I would like to talk about cachexia and food in general in relation to pancreatic cancer.

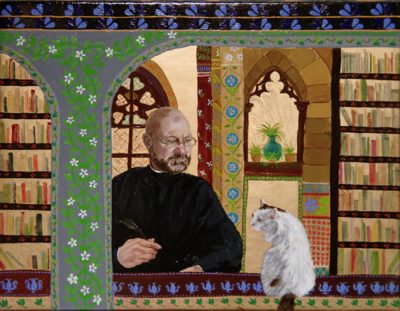

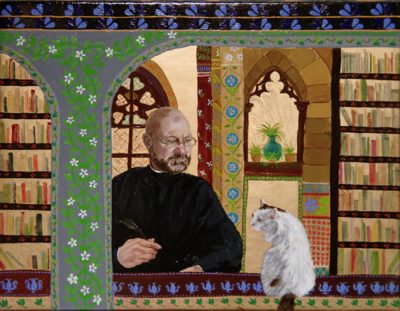

In this story, I will not use my husband’s name, as he was a private person and would not have wanted the attention. But I feel it is important to talk about what happened, so that others can be aware of cachexia. He also disliked sharing his photo, so the picture is one I painted of him with our cat (with him posing as St Jerome!).

He was quickly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer

My husband was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in August 2020 and died in February 2021. Prior to diagnosis he had few symptoms: some indigestion in July. The only other potential ‘sign’ he might have had is night sweats, which he had had for years and progressively became worse as his disease progressed.

His GP thought the indigestion required further investigation so a few weeks later he had an endoscopy where they saw a tumour, and did a biopsy. One week later he was jaundiced.

The verdict came back, locally advanced head of pancreas cancer with involvement of the blood vessels, so inoperable.

He started a course of chemotherapy after a biliary stent was fitted. He had infection after infection, so the chemotherapy was not pursued. He also underwent blood transfusions, bypass surgery, and more.

He needed to eat well to maintain weight

He was in and out of hospital, not the best place for fine food. This was all during the COVID lockdown, impeding our visits and the chance to take food to him.

With pancreatic cancer especially, much is made about maintaining weight to enable quality of life and survival. The statistics speak for themselves: weight maintenance is correlated with both, so you quickly grasp the importance of food as a tool, not just a pleasure. The snag we discovered was that this can quickly spin completely out of your control.

We thought we had it covered

My husband was a ‘foodie.’ We loved experimenting with food, and he was the main cook of the house, his tastes firmly in the world of classic French food he grew up on. I grew up loving food too, raised on multi-cultural dishes and plenty of spices.

Even with a potentially life limiting diagnosis, our reaction to the concept of food and cancer treatment initially was ‘we have got this covered.’ We had a rosy picture that even in the event of his needing palliative care, we could enjoy nice dinners till the end.

I had had experience of food issues and chemotherapy as my mum had had breast cancer. So I knew some tricks of the trade, such as eating with ceramic spoons (found in Asian shops) to counter the metallic taste, having small portions of tasty things, and so on. As a family, food is central to our life.

His digestive problems made eating very difficult

However, food quickly became a massive issue as his digestive system was affected. The impact on the digestion was enormous. He was prescribed digestive enzymes, food supplements, saw a dietitian, was given guides on what to eat and how important it was, and yet…

It is hard to unravel how cachexia (extreme loss of muscle and fat) starts and takes grip. My husband experienced lowered digestive ability, stents, bypass surgery, a change in gut biome (which could not be countered through probiotics), heavy antibiotics, chemotherapy, infections and a fever, and thrush in the mouth.

For him, eating became a struggle physically: even swallowing the digestive enzymes was difficult, let alone all the other medications, injections of blood thinners and the rigmarole of treatments that might have an appetite reducing effect.

As his appetite diminished and the disease progressed, a combination of nausea, feeling full, and depression created a perfect storm where he became weaker, vomited more dramatically, and could not face food. You wash your mouth with bicarbonate of soda, suck ice lollies and hope for the best.

The struggle with food is hard on people with cancer, and on carers too

For the carers it becomes a never ending round of trying to source tasty and easily swallowed food, cooking tempting meals, and trying out new recipes.

For the person with cancer, it is a battle to force themselves to eat. We had tears when previously loved items could barely be swallowed, with desperate attempts at forcing down gag-inducing nutrition drinks to combat weight loss, as the medical mantra was to prioritise calorie intake.

The general medical advice was to ‘make an effort’ to eat. In our case it made everyone feel bad, as if they were not trying hard enough, perhaps a side effect of the dreaded ‘battle talk’ surrounding cancer. Yet my husband tried, all the time. It became an obsession, not just for him but everyone around him seeing him waste away. After all, are we not hard wired to nurture and feed our loved ones?

I wish we had known about cachexia sooner

Finally, I came across the concept of cachexia. Sadly, this was only after he died. No one in the medical world had mentioned it, and it suddenly made sense to all of us who had cared for my husband as to why we had faced this struggle. Knowing about this created a huge relief for our kids, who had been so worried that we had failed my husband by not feeding him enough.

I get why it is not mentioned: it might lead to a defeatist attitude. But I would argue that knowing about it would alleviate guilt and enable you to concentrate on quality, not quantity, of food. When faced with limited eating ability, my husband would rather eat small amounts of tasty stuff for a few weeks than force horrid high calorie drinks down for a few months. I feel the choice around that should be available to patients and their families, even if the outcome is stark.

There is no ‘cure’ for cachexia. It is more a kind of systemic syndrome than a condition in itself and we were told that in his case the only management for it was food and exercise. But both of those things were impacted by cachexia as it reduced his appetite and muscle mass, so it was like being caught in a negative loop. For my husband, the appetite loss was beyond normal appetite loss. It was almost a physical inability to eat, where eating a mouthful led to gagging and vomiting.

We need more awareness of cachexia for people at the end of their life

Perhaps it is because some appetite loss is ‘normal’ with cancer, it seemed to me that cachexia was difficult to diagnose. However, I hope more studies in this poorly understood area will help patients in the future.

To me, cachexia should be publicised widely. The more it is known about, the more research can be done into it. In the meantime, I was glad that Pancreatic Cancer UK made it possible to publish this story on their website when I talked about it to them after my husband’s death.

I want other carers reading this to know that cachexia is ultimately beyond your control and that you are not failing as a carer if your loved one cannot eat. It is awful, demoralising, but you and the person with cancer should stay clear of negative notions such as ‘not trying hard enough.’

Enjoy eating what you can, when you can, food hopefully made with love and eaten with joy even if for a short amount of time.

February 2023